“The old man use to say the best parts about hunting and fishing were the thinking about going and the talking about it once you got back.” Robert Ruark

For Christmas this year I received a book titled All About Elk written by elk hunting pioneers Mike Lapinski, Dwight Schuh, Wayne Van Zwoll, and Duane Wiltse— published in 1987. The 80’s were an interesting and important time period for how elk were hunted. Calling was becoming popular, and tactics for bowhunting were changing as compound bows increasingly replaced recurves. Concepts like cow and calf calling were new and controversial. The average hunter didn’t know when or why a bull bugled, and the very best optics available could be outperformed by some of the lowest quality made today. There weren’t many elk calls for sale. Mike Lapinski used a turkey call and the tube from his wife’s vacuum cleaner and “got ran over by elk and bowhunters alike.”

Much has changed and much has not, and a book like this is a time capsule for how things were. Also within these pages are hard-earned lessons that have been forgotten by most, written by some men who are no longer among us.

In 1987 compound bows didn’t act as they do now. In a section about hunting in cold weather, Lapinski writes, “A bow will act sluggish when the temperature is zero…at 30 yards, you will consistently hit a foot below the target. Remember to place your sight pin a little high on an elk to compensate for this drop.” Bows and sights have gotten so precise today that I was on a call recently discussing how density altitude affects arrow trajectory, something that most in the archery industry declared a myth as little as four years ago. Many of the archery manufacturers that were in the game then are still in it today: Hoyt, Martin, PSE, Darton, and Bear to name a few.

Dwight Schuh writes that elk are big heavy animals and bows with draw weights of 60-90 lbs are ideal. He suggests shooting the heaviest bow a hunter can handle well. “Arrow size and composition are not overly critical to the elk hunter.” Here’s a statement that did not age well. During the 90’s hunters shifted from cedar, fiberglass, and aluminum arrows to lighter and lighter carbon arrows. Hunters wanted to be able to shoot farther, and range estimation was just that, estimation. Laser ranger finders were just starting to become available but they were bulky, expensive, and unreliable. Defeating range estimation meant increasing velocity through overdraws, lighter arrows, and various other sins against penetration. With bow sights like the Garmin Xero, precision-made broad heads, and excellent affordable rangefinders, archers are currently trending toward heavier arrows because they are better at killing bulls. Arrow composition matters very much with today’s technology.

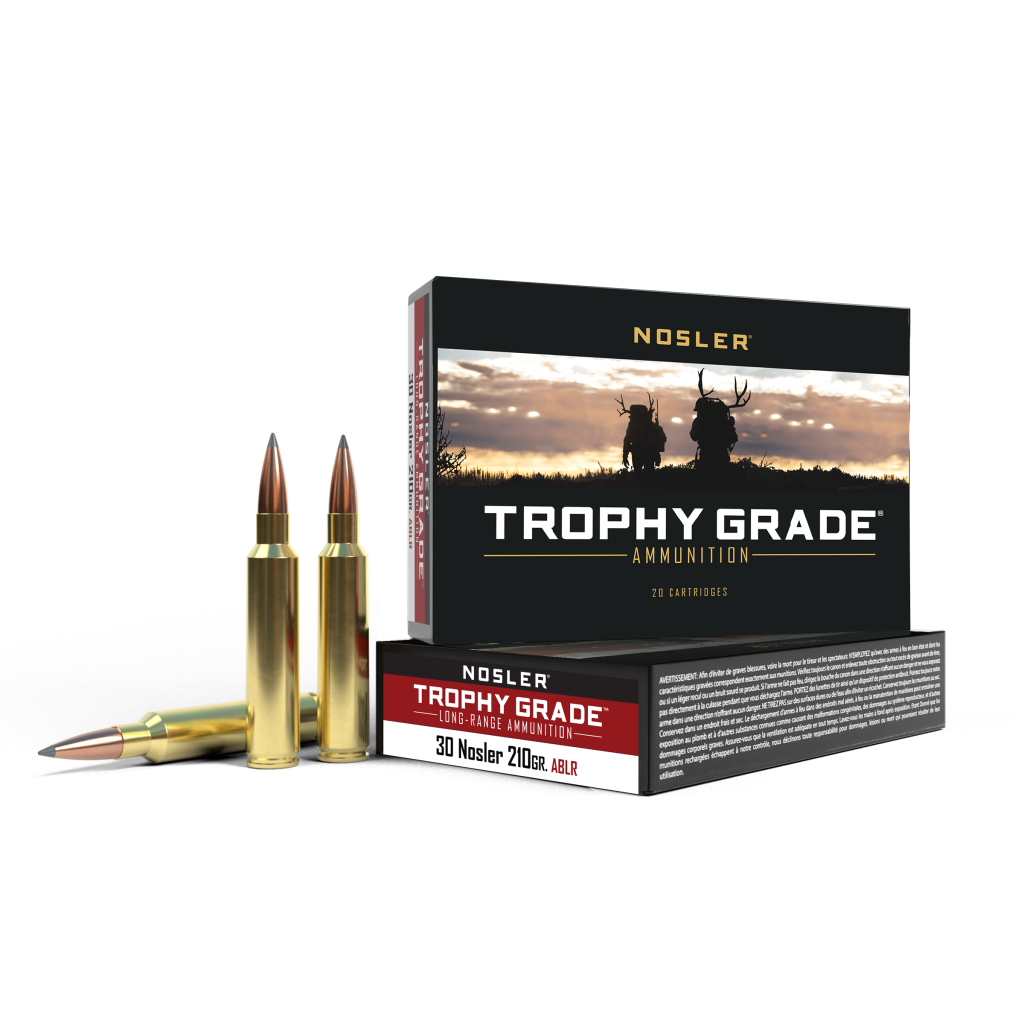

The section on elk rifles is also very interesting. It lists the top 6 elk cartridges as the 270 Win, 308 Win, 7mm Rem, 30-06 Springfield, 300 win mag, and 338 win mag. The 270 is described as adequate in the hands of a skilled shooter but on the lightest end of the spectrum that a reasonable elk hunter would choose— also a good choice for the synthetic stock mountain rifles that were becoming popular. The 300wm is for the “serious sportsmen who do a lot of elk hunting,” and the 338wm is for the elk hunter who might also want to hunt grizzly or moose someday. In the past 35 years, little has changed in this department except that bullets have become much more consistent in both their accuracy and performance. Cartridges like the 28 and 30 Nosler have stepped up in recent years and may have dethroned my beloved belted magnums, but the recipe of a well-constructed 200+ grain bullet traveling at least 2900 feet per second out of the muzzle remains solid for bull elk on any hillside I’ve ever hunted.

The method for sighting in an elk rifle described in the book is to start by getting your bullet to impact 1/2” low at 25 yards, then to get a group 3” above the target at 100 yards. Now you will have something that drops 30” at 400 yards, so you only need to hold on to the animal’s back to get a perfect hit. Thankfully we don’t live in those ballistic dark ages anymore. I grew up during this time and made shots on elk that I’m embarrassed to describe now because I know how much luck was involved and how much risk of wounding I was unknowingly accepting for the animal. Today, I can use a SIG rangefinder to determine the density altitude, range to the target, shot angle, target location, how fast my bullet will be traveling on impact and how many foot-pounds of energy remain in the projectile simply by pressing a button. I can then dial a turret or use a reticle to hold exactly how high I need to make sure of a precise shot. Now, I still don’t take very long-range shots on elk for a number of reasons, but any time you are holding off the target, say, beyond 270 yards, you had better know exactly how high to hold. An animal’s life is not something to gamble with.

Many backcountry hunters today embrace suffering like a participation prize, but in ’87 these men only endured as much harshness as was required. They include a section on how to take a daily bath or shower, regardless of the temperature outside. After which they suggest getting into a five-pound sleeping bag. Their elk hunting survival kit includes a space blanket, 1 day of dried food, waterproof matches, 20’ of rope, 8 ounces of juice, and a fire starter tab.

In the section regarding physical fitness, they used my home mountain range (now almost void of elk), as the setting for an anecdote of a doctor who considered himself fit but nearly died while trying to navigate the steep terrain on his first elk hunt. The following year he ran three miles a day, went from 160 to 130 pounds, elected to hunt Idaho instead of Oregon, and got himself a bull. Fitness is important in elk hunting today, but less so than the internet would have you believe. You need to be able to hike 4-6 miles a day in steep stuff, and if you plan on packing elk out on your back, I suggest getting good at squats and lunges. I’ve rarely found running to be helpful while elk hunting unless it’s to the nearest bush with toilet paper in hand roughly 72 hours after eating Mountain House. Still, this book suggests a man in his thirties be able to run 1.5 miles in 10:00 minutes before he consider himself ready to hunt elk. If I had to choose between being fit and being patient I’d choose the latter, but ideally, an elk hunter possesses both.

On calling, the authors write, “The fact is, bulls do bugle, which helps to locate them, and they do come to a call, which helps you to get a shot.” I dare someone to argue against this point. Elk speak a language that hunters are constantly trying to decode, and we are getting better at it. However, it would be as difficult for me to write about the nuance between a cow bark and a bull bark as it would be to describe the color green to Helen Keller. You have to get out there and learn for yourself.

Dwight Shuh, one of the authors and a veteran of the Vietnam conflict, passed away in 2019 from complications following exposure to Agent Orange. I was able to reach Mike Lapinski, who has continued writing but shifted his focus to animals like bear, jaguar, and ocelot. He may be best known for writing about Timothy Treadwell, the guy who mistook a brown bear for a friend.

I asked Mr. Lapinski what he believes has changed in the last 35 years.

Mike: “My goodness. Technology. It was unethical to take a 40-yard shot with a bow back then. And the elk weren’t as pressured. Most of the elk I called to had never been called to by a man before. You know, the closer you get to a bull, the more sensitive he becomes. Shooting accurately from a longer distance means a big advantage. Elk aren’t smart, ya know. They can’t count to ten. But if you kick a dog in the belly and call him to you, he isn’t going to come. And that’s how elk are today with the pressure from people in the backcountry. Places where people would call you a liar for saying you saw a grizzly then are full of them now. Grizzly in every draw in lots of western Montana.”

I’ve shot elk with bow and rifle and pistol from all kinds of ranges. I can tell you with certainty, that closer shots are both more lethal and memorable. Should you learn how to shoot 40 and beyond with a bow? Absolutely. But you should also learn how to get closer because the difference in how you feel with a bull elk at 30 yards and a bull elk at 8 yards is incomparable.

Some technology has changed and some has hit a glass ceiling and remained much the same. Elk have changed their behavior due to pressure from hunters, changes in migration corridors, climate, and predation but a time traveler who consistently killed bulls in the 80’s would be able to do so again today. I encourage folks to pick up “old” books like this and see what treasures of information they have on their pages. Not every piece of knowledge shows up in the first page of a google search. Let this be a new kind of hunting for you this winter, a hunt for lost knowledge.