A wide racked, deep-forked mule deer buck climbed the face of a far ridge, almost to the top and gone. My friend, an expert shot with any kind of weapon, lay prone behind his rifle, scope trained on the buck as it climbed.

“Range?” The word was terse and unembellished with superfluous verbiage. Leaning away from my spotting scope I steadied my rangefinder on the buck.

“Nine ninety-three”. I said. “No wind.”

Back in the spotting scope, I watched as the buck halted for a breather. Seconds crawled by with tortoise-like velocity as I waited for the vapor trail. Then there it was, preceded a millisecond by the boom. Arcing high above the buck’s back the trace curved steadily downward. “Just a hair high”, I thought to myself, and the poof of dust erupting from just beyond the buck’s back proved me right.

“Right over his back”. I said. A second cartridge had been slammed home in less time than it takes to tell about it, the shooter already settling the crosshairs for a follow-up shot. I stayed in the spotting scope as the buck took a couple startled jumps forward and stopped. Then there was the second trace, and before it reached the buck I knew he was dead. Dropping at the impact, the buck kicked a couple times, slid down the slope a bit, and lay still.

Hunting at long range is an increasingly popular sport. Rangefinders, optics, ammunition, and rifles are more capable than ever before. With the right equipment, 600 yards is the new 300. But the problem with these changes is that too many hunters think they can simply run to the nearest sporting goods store, buy a “long range” rifle, top it with a “long range” scope, and go shoot an elk at 800 yards.

It’s not that easy.

To be proficient at long range shooting, let alone hunting, you must develop a vast collection of knowledge, skill, and experience. With that in mind, let’s talk a closer look at some of the “Do’s and Don’ts” of hunting at long range.

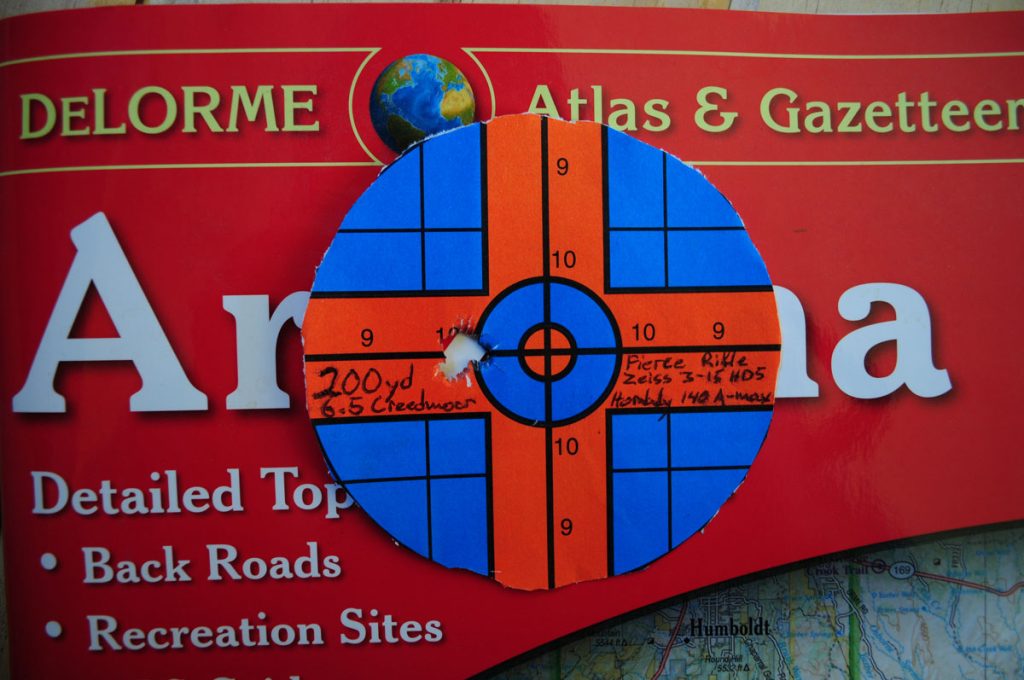

DO: Use a capable rifle, optic, and caliber. The gun should hold under one-minute accuracy, the scope should dial accurately and reliably, and possess a zero-stop. Ammo should be very accurate and bullets should boast a very high Ballistic Coefficient, as well as reliable expansion characteristics within a large velocity range.

DON’T: Expect your old faithful wood-stocked 30-06 with its 3-9X40 scope to work for long range shooting. I’m totally enamored with such rifles, and they’re awesome hunting guns, but they’re simply not right for long range shooting.

DO: Know your rifle. That statement includes the whole package: rifle, scope, ammo, and ballistic data. You must know exactly where your system shoots at every distance. If you want to make lethal hits at long range nothing can be left to chance.

DON’T: Trust that someone else’s dope will work for you. Every person’s eye, cheek weld, body tension level, trigger squeeze is different. You’ve got to verify the zero as well as the ballistic data on a rifle before you hunt with it.

The spotter’s job is important – his responsibility is to read the animal, make a wind call, and spot vapor trail and impact.DO: Always hunt with a spotter. No matter how good you are, never take long shots without an experienced buddy spotting for you. He’ll read the wind, give you heads up on any changing conditions, and call your impact and correction for a follow-up shot, if necessary.

DON’T: Shoot without permission. Make sure your spotter has his eye in the scope and is expecting you to shoot. A quiet “Ready” or “Send it” from the spotter will give you the green light. Establish communication protocol during practice sessions, so you both know what to expect.

DO: Get a perfect range reading. Often it’s very hard to get the exact range to your quarry. Laser nearby rocks, trees, and other animals to verify your read to your target. Even a 20-yard misread at an extended distance can mean the difference between a hit and a miss.

DON’T: Shoot in high wind. Even if you’re really good at reading wind, be very cautious about sending a shot at an animal through it. Try this: next time you experience 20-plus mph gusty wind conditions, go out shooting. If you can hit a 12-inch deer-sized vital area every shot at, say, 750 yards, you belong on an Olympic shooting team, not hunting deer.

DO: Be aware of your projectile’s limitations. For example, the 6.5mm 143-grain Hornady ELD-X bullet (one of my favorites) is advertised to expand at velocities down to around 1,800 fps. Shot from a 6.5 Creedmoor at my home elevation of 6400 feet, that occurs somewhere between 800 and 900 yards. Beyond that, the bullet won’t open reliably or kill cleanly.

DON’T: Take a chancy shot just because it “might work”. There are no excuses for taking shots that are too far or too windy or a bad angle or anything else of that nature, just because there is a chance it will work out and you will have awesome bragging rights. That kind of behavior is unethical.

DO: Get perfectly steady. Establish the best position you possibly can before making the shot. If you can’t keep the crosshairs inside the vital zone, adjust your position until you can. Only then should you take the shot.

DON’T: Take your gun off an animal that drops in its tracks. If you’ve hit him high – just above the spine – he might drop like he was hit by a train, only to get up and march away when the shock wears off. Keep your crosshairs on the animal until you’re absolutely sure he’s dead.

DO: Turn your scope DOWN. That’s right, I said down. Scopes with magnification big enough to read the morning paper from a half-mile away are all the rage. But for hunting, they are a handicap. Out to 500 yards, nine or ten power is ideal and will enable you to spot your impact; assuming you do everything else right. Even at 800-plus yards, anything over 18 power is too much. Spotting your hit, and keeping the animal in your scope to watch him drop or make a fast follow-up shot is far more important than counting his eyelashes.

CONCLUSION

Early in this article, I stated that “600 yards is the new 300”. With the right equipment, training, and experience, it’s true. That said, six-hundred is, in my opinion, the maximum distance most well-trained hunters should shoot at living animals – just as 300 used to be. Most hunters simply don’t have the ability to put every shot into the vitals beyond that, even with extensive practice. To my point, consider this; I shoot and hunt for a living. I believe I could – with the right rifle – cleanly harvest an animal beyond 600 yards. But I still try to get close, and to date, my furthest shot on an animal was exactly 586 yards.