A worn game trail weaved between the rock outcroppings on the edge of the plateau and the flat where juniper and fir trees grew from the thicker soil. It had snowed enough two days earlier to wet the dust from summer and fall. I tried to find a distinguishable track and did– a splay-footed bull whose hooves had been worn down in the front more than most. I walked along a few feet to the side of the trail until I saw the track again, this time headed in the opposite direction. I continued into the timber until the trail I followed intersected another worn into the earth. Being careful not to walk on either of these I looked for and found a thick red fir tree and backed into it, hung my pack from a broken limb, and checked the wind for the 63rd time that evening. I drew my P320 XTEN 10 mm from my Eberlestock bino harness, did a quick brass check, and then quietly pushed the slide back into the battery.

I waited for half an hour, listening and letting the woods settle down. When I started calling it was mellow, just a single cow call every five minutes or so, nothing too pleading or emotional. After the third set, a bull responded with an aggressive bugle from a couple hundred yards away. I drew my pistol and rested it on top of the bino harness. I could feel my heart hammering through the grip of the gun. The bull walked in slowly, a great mature 6×6, and not at all what I was looking for.

This may sound strange, but I get to hunt lots of mature bulls with my clients during archery season, so when I get the chance to hunt for myself I target bulls with a higher meat quality, which means younger animals. Very few honest hunters ever say they prefer the meat of old bulls to young ones.

Three younger bulls followed the 6-point, including a big-bodied and small antlered five by five. The mature 6×6 had come in at around 30 yards for a few minutes then walked out to the 60-yard range, looking around for the cow he had heard. When the raghorn 5 point got too close to him he dropped his antlers and slammed into the younger bull broadside, hitting him in the neck and ribs with his fourth tines. The raghorn wheeled away and stopped at around 30-35 yards from me. I pushed the 10mm forward, tucked my chin, settled the sight, and pressed the trigger.

The ammunition I used is made by a family-owned business in the Pacific Northwest called G9 Defense, and if not for the distinctive capabilities of this stuff, I wouldn’t consider trying to kill a 600lb animal with a 10mm. But this ammo doesn’t behave the way other pistol ammo does.

The solid copper 145-grain bullet exited the muzzle of my pistol at 1,380 feet per second. The bullet impacted 1/3 of the way up from the bull’s chest, cut a 10mm sized hole through the hide, broke a rib, went through his right lung, the blood vessels above his heart, the left lung, another rib, and piled up against the skin on the far side. He ran 20 yards, abruptly laid down, and was dead in less than a minute’s time from the firing pin striking the primer. My heart beat so hard I wouldn’t be surprised if it caused a seismic event on the far side of the world.

The origins of this projectile are interesting. Some years ago Joshua Mahnke, the owner of G9, received a phone call at 3 am from someone with a stiff accent asking for a pistol bullet to use against polar bears. That’s got all the makings of a prank call, and was regarded as such. But they called again during business hours and it seemed there was a legitimate need. The person calling was from a Scandinavian military unit that was required to operate in polar bear country, and during some of their missions, they were only able to bring pistols. They needed a 10mm bullet that could penetrate a polar bear’s skull. Mahnke went to work, starting with a glass-breaker design and ending up with the patented G9 Woodsman. Bear skulls have a geometry that makes penetration difficult for many pistol bullets. They tend to go under the skin, and then glide around the bone rather than penetrate.

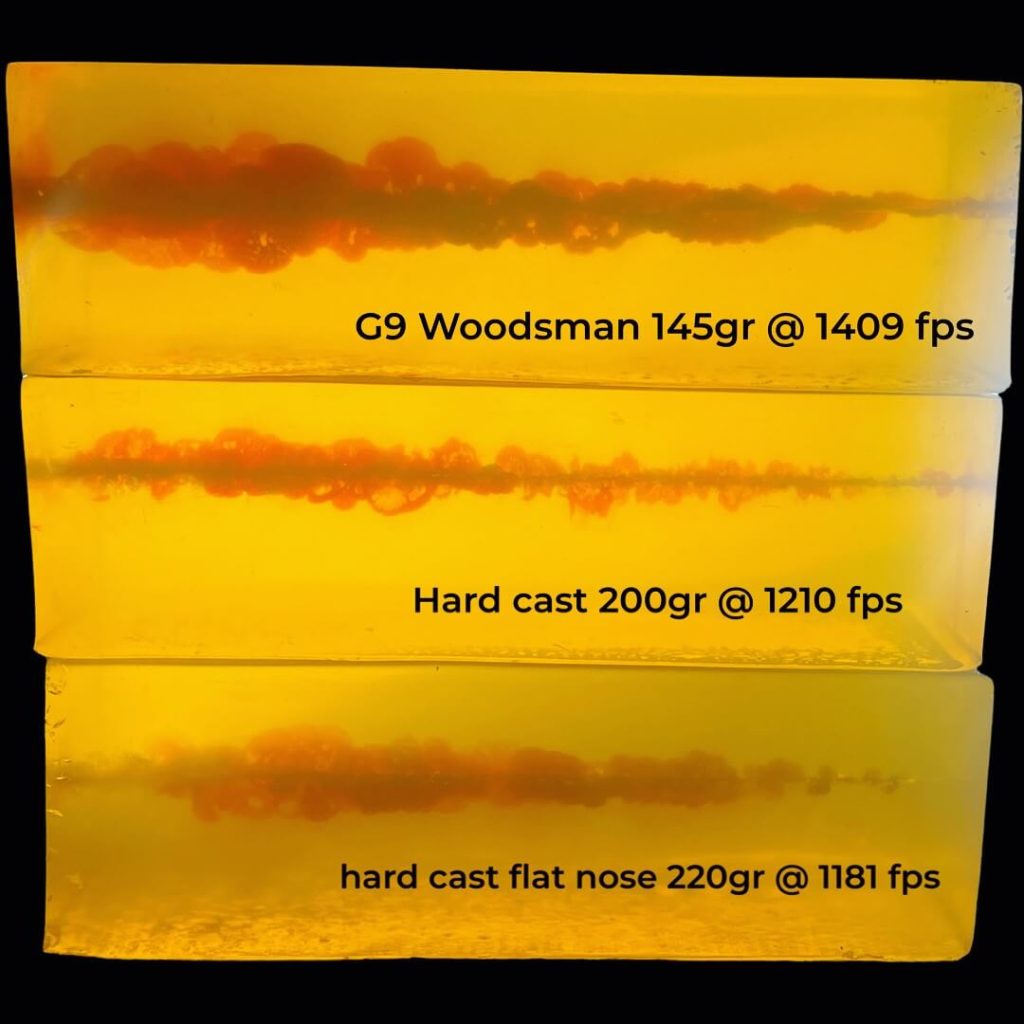

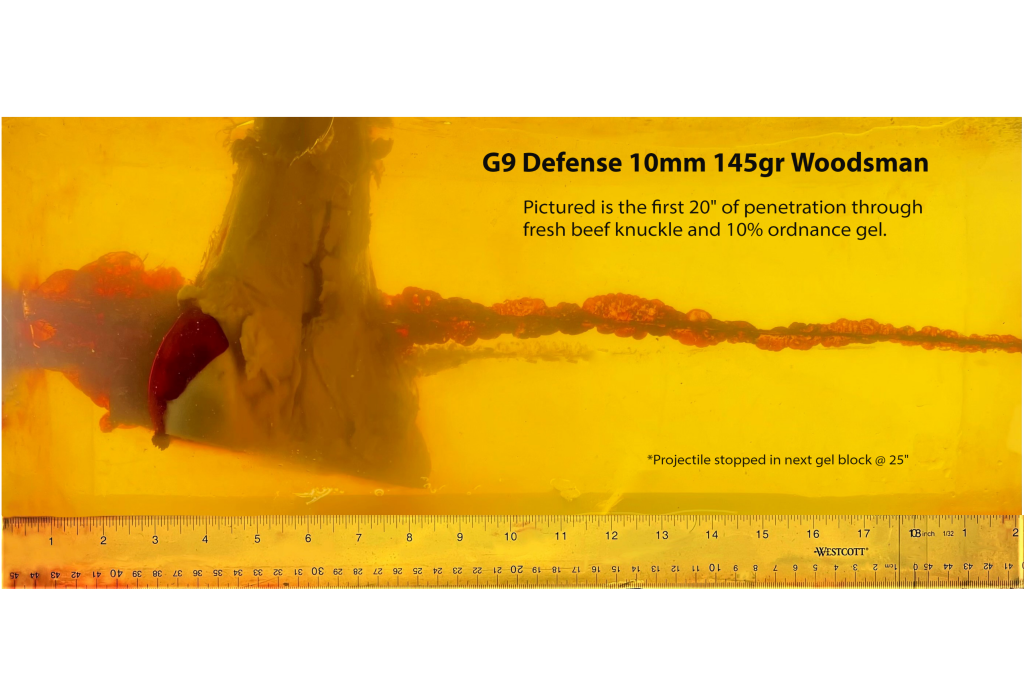

The Woodsman is an outlier. When we think about 10mm bullets our brains tend to start at 180 grains and head North from there. I was skeptical, to put it mildly, about a 145gr bullet. The ballistic gel tests showed me something interesting. The Woodsman penetrates the same distance as a 200gr hard cast lead bullet, around 46 inches. There are a couple of significant differences though. The first is on the shooter’s end because there is 30% less felt recoil due to the projectile being significantly lighter and requiring lower pressure. If we are talking hunting or defense, follow-up shots need to be part of the conversation, and recoil slows that conversation down. Next, we have the trajectory, which is flat for all the distances I can shoot effectively. That means my hold at 20 yards and 50 yards is the same. I tend to start missing past 50 so that’s my limit for hunting, but it’s pretty fun to shoot steel at 100 and beyond with this ammo. Finally, we and the bullet arrive at the target, and this is where things get really interesting.

Conventional hollow points cause damage by crushing or tearing the tissue which comes into contact with the bullet. When you start adding hair, hide, and bone these hollow points start to experience rates of failure above 40%. Hard cast lead and semi-wad cutters do the same thing except for an effect called “Solid Metal Fluid Transfer” or SMFT. These projectiles “cast off” fluids in the area around the bullet and cause damage in a radius around the path of the projectile that is related to the speed of the bullet and therefore the speed of the fluid it displaces. Picture water moving away from a boat as it travels through an area with lily pads– at low speeds the lilies brush along the hull of the boat, at high speeds the lilies are cast off to the side in the wake, and at extreme speeds, the lilies are torn from their stems.

Fluids traveling at 140 feet per second destroy tissue. The G9 solid metal bullets “cast off” fluid at 30% greater than projectile velocity. This is sufficient to turn the liquid in organs and blood vessels into a compressive jet, destroying tissue in a large radius around the path of the projectile. All this to say that since the 145gr Woodsman is going fast, it creates a large wound channel and penetrates deeply. It is able to do this because copper is harder than hard-cast lead, because of the shape of the Woodsman, and because it’s going a hell of a lot faster than its 200gr cousin.

A hard cast solid tends to create a wound channel about 25% larger than the bullet’s diameter, the Woodsman creates a wound channel as large as 2.5 inches. Additionally, it continues driving straight after hitting bone, and doesn’t require a change in shape in order to function like a hollow point. A decrease in velocity once it hits a target tends to be linear.

When non-toxic ammo hit the streets my observations were that a better name for it would be “Less Lethal” because it just didn’t kill as well as what I was used to. I said then that I wouldn’t shoot the stuff until it became “More Lethal” and that’s exactly what has happened in the case of the G9 Woodsman 10mm. Is it the ideal elk cartridge? Hard no. Is it the most lethal option against large animals from a 10mm? Yes.

As you shed winter, many hunters, nature walkers, turkey hunters, and other springtime enthusiasts hit the woods where bears are coming out of hibernation and cougars are feeling sassy. You might consider carrying ammunition that shoots flatter, hits harder, and kills quicker than anything else. This is the stuff.